|

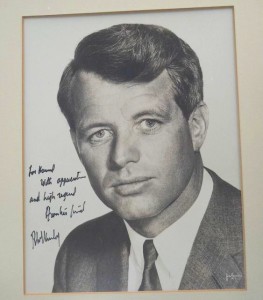

MORE ABOUT ROBERT F. KENNEDY AND THE WARREN COMMISSION |

|---|---|

| After I responded to Philip Shenon’s article about Attorney General Robert Kennedy being a “conspiracy theorist,” other commentators weighed in on the general subject of the Attorney General and the Warren Commission. Several did not accept my conclusions; others expressed understanding of why the Attorney General would prefer not to testify before the Warren Commission. I think it is useful in discussing this issue to disentangle the three separate questions that are raised by this discussion. These are: (1) Did Robert Kennedy refuse to provide the Commission with a sworn statement that he was not aware of any evidence of a conspiracy that resulted in the assassination of the President? (2) Should Robert Kennedy have provided the Commission with the information he had regarding the CIA’s plans to assassinate Castro? and (3) At the time he was assassinated in 1968 did Robert Kennedy believe that his brother’s death was the result of a conspiracy contrary to the conclusion of the Warren Commission. I will address only the first question in this discussion. |

|

Philip Shenon claims Robert Kennedy was a "Conspiracy Theorist" |

|

| Did Robert Kennedy refuse to provide the Commission with a sworn statement that he was not aware of any evidence of a conspiracy that resulted in the assassination of the President? As I previously stated, my answer to this question is “No.” Let me explain why. As of mid-May 1964, the Commission had heard dozens of witnesses and needed to decide which witnesses should be asked to testify in the next few weeks. After canvassing the staff, Rankin submitted a memo (which I drafted) dated May 13, 1964, to the Commission that listed 12 candidates to appear before the Commission, with a few words identifying what each of these witnesses might contribute to the Commission’s work. The full list was as follows: J. Edgar Hoover and John McCone (“Relationship with Oswald and current state of investigation”); Mrs. John F. Kennedy (“Events of November 22, 1963″); Robert F. Kennedy (“Evaluation of investigation”); Sgt. P.T Dean (“Conversation with Ruby on November 24″); Dist. Atty. Henry Wade (“Events of November 22-24 and evaluation of current investigation”); Marina Oswald (“Various additional matters regarding her husband”); Chief Rowley (“Presidential protection”); FBI Agent Shaneyfelt, Ronald Simmons (and possibly Agent Frazier again) (“Approximations of distances and locations after Dallas Project [the reenactment]. Additional tests with rifle in light of any new data produced as a result of Dallas project.”); Nosenko and Jack L. Ruby (“These witnesses both raise special problems which should be considered further by the Commission.”) I believe this memorandum demonstrates that as of May 13 Rankin and I (and perhaps other members of the staff) believed that Robert Kennedy might appear before the Commission. The Attorney General had not told me that he did not wish to appear before the Commission and no one else at the Department had expressed this view on his behalf. If Rankin had received any such message from Warren or anyone else, he and I would have discussed it before including Robert Kennedy’s name on the list of prospective witnesses. The Commission met on May 19, 1964. Rankin issued a short memo after the meeting stating that the Commission had discussed “the taking of further testimony.” If such a discussion took place, it was not in the presence of the court reporter because the 55-page transcript does not record it. (The reported discussion at the meeting related solely to consideration of security clearances for two members of the staff about whom questions had been raised.) I assume that Rankin and Warren had a discussion after the meeting on this subject (perhaps with one or more Commission members) or in the next few days before I met with Rankin on May 22. They obviously concluded that Nosenko should not be a witness, that the Commission should travel to Dallas to hear Ruby if he was willing to testify, and that I should be instructed to consult with the Attorney General about arrangements for taking Mrs. Kennedy’s testimony and about his own “statement”. As reflected in my journal entry of May 22, Rankin instructed me along these lines. Rankin said nothing to indicate that Warren had talked to Robert Kennedy on this subject either before or after the Commission meeting on May 19. What the Commission wanted from the Attorney General (and other agency heads) were assurances on two matters; (a) all relevant information pertaining to the assassination in the possession of the department or agency had been delivered to the Commission; and (b) the agency head had no information regarding the existence of any conspiracy that led to the assassination. I am not aware that any member of the Commission or its staff expressed an interest in having testimony by the Attorney General on any other aspect of the investigation; and Rankin at our meeting on May 22 did not express any different view. I believe that my initial meeting with Ed Guthman on May 28 (as described in my June 4 journal entry) supports my view that the Attorney General had not told Warren that he did not wish to appear before the Commission. I believe that Guthman would have known of any such conversation if it had taken place. As my journal note indicates, Guthman and I discussed the possibility of Kennedy’s testifying before the Commission as well as the alternative of a statement by him that would address the concerns of the Commission. On June 2 Guthman told me that he had discussed the matter with the Attorney General and asked me to prepare a statement along the lines we had discussed. I drafted the statement found in the Commission files. I do not know why I included the reference to the Attorney General being “sworn” in the first sentence. Rankin had clearly said “statement” and not “affidavit.” The document is entitled “Statement” and does not include the standard concluding statement in any affidavit that the witness “swears or affirms” that the facts contained in the document are truthful. All I can conclude is that I made a mistake — neither the first nor the last in my professional life. I took this statement to my meeting on June 2 with Guthman and Katzenbach. They rejected the statement that I had prepared as “sterile and unsatisfactory.” There was no discussion of its reference to the Attorney General being “sworn.” As a result of this decision, the Attorney General never saw the statement I had prepared. It was at this meeting that Katzenbach proposed the “third alternative” of an exchange of letters. Katzenbach did not tell Guthman and me that he had discussed the Attorney General’s appearance before the Commission with any Commission member or, indeed, with the Attorney General. His view simply was: a letter from the Attorney General would address the Commission’s concerns effectively and remove the need for any further personal involvement by the Attorney General in the Commission’s work. When we met with the Attorney General on June 4, he did not tell us (or indicate in any way) that he had told Warren or any other member of the Commission that he did not wish to appear. If he had done so, I believe he would not have discussed the possibility of testifying before the Commission as one of the alternatives under consideration at our meeting. He stated that he would do whatever the Commission wanted him to do. He stated that he recognized the desirability of having a statement from him to the effect that he had no evidence of a conspiracy and that the Department of Justice had provided all the relevant information in its possession regarding the assassination to the Commission. At Katzenbach’s request, I had prepared a draft letter from Robert Kennedy to the Commission which he reviewed at the meeting. He suggested one modification reflecting the fact that he had not received any reports from the FBI regarding the assassination. After further discussion, he approved the exchange of letters as a preferred manner of addressing the Commission’s concerns. Following the meeting, I wrote a memo to Lee Rankin reporting on my meeting that day with Katzenbach and the Attorney General and the proposed exchange of letters between the Commission and Robert Kennedy. I did tell Rankin that “The Attorney General would prefer to handle his obligations to the Commission in this way rather than appear as a witness.” I told Rankin that the proposed response by the Attorney General to a letter from the Commission had not been approved by him or on his behalf by Deputy Attorney General Katzenbach. On June 11, 1964, Warren on behalf of the Commission wrote the Attorney General asking (a) whether he was aware “of any additional information relating to the assassination of President John F Kennedy which has not been sent to the Commission”; and (b) whether he had “any information suggesting that the assassination of President Kennedy was caused by a domestic or foreign conspiracy.” On June 12, 1964, I sent Katzenbach a copy of Warren’s letter to the Attorney General and provided a revised draft response from Kennedy to the Commission. I wrote Katzenbach regarding the draft response: “The letter is completely satisfactory to Mr. Rankin and the Chief Justice, and the Chief Justice feels that such a response will eliminate any need to call the Attorney General as a witness before the Commission.” The approach followed by the Commission with respect to the Attorney General was not unique. The Commission asked for, and received, non-sworn statements from President Johnson and Mrs. Johnson about the events on November 22, 1963. In addition, the Commission report (page 384) listed several US officials who agreed with the Commission’s conclusion that there was no evidence of a conspiracy. Most of the officials named had testified before the Commission — Secretary Dillon, Secretary Rusk, Hoover, McCone, and Rowley — and had expressed their conclusion to this effect during their testimony. However, Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara, did not appear before the Commission and provided his statement regarding the lack of evidence of a conspiracy in an unsworn letter to the Commission, which is Exhibit 3138 in the Commission’s records. Based on these facts, I conclude that (a) the Commission never asked the Attorney General to provide sworn testimony regarding the lack of evidence regarding any conspiracy; (b) the Attorney General never saw the draft “sworn” statement I prepared; (c) he therefore never refused a request for sworn testimony; and (d) The Commission’s acceptance of his non-sworn letter addressing the Commission’s two basic concerns was fully satisfactory to the Commission and consistent with its practices. POSTSCRIPT: THE DELAY IN THE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S RESPONSE Some commentators have found it “curious,” if not “suspicious,” that the Attorney General did not send his letter back to the Warren Commission until August 4, 1964 – some seven weeks after he received Warren’s letter. They obviously had not read the following discussion of this issue at page 192 in my book: “ I met with Katzenbach on June 17 to follow up on Mrs. Kennedy’s testimony and the attorney general’s response to Warren’s letter. I told him: ‘I would prefer that the letter not be answered immediately.’ By way of explanation, I mentioned that ‘I expected there would be a considerable difference of views between the Chief Justice and the staff regarding the quality of the report.’ If this situation developed, I told Katzenbach, ‘I intended to fight for a report I considered satisfactory, and indicated that a delay in sending this letter would bolster my position.’ Katzenbach said that he would hold the letter while the attorney general was in Europe from June 23 to June 30. I had no reason at the time to believe that Warren (or the other members of the commission) might try to limit the investigation or shape its conclusions in a way that would be unacceptable to me or other members of the staff. I may have been thinking of our difficulties with the Treasury Department on presidential protection issues. But I was obviously anticipating the worst, and being able to employ the persuasive force of the Justice Department and Robert Kennedy, if necessary, was a precautionary step that seemed appropriate at the time.” I never spoke with Katzenbach again about Robert Kennedy’s response to the Warren Commission. I do not know the circumstances under which the letter was presented to him for signature on August 4. I do know that this was an incredibly busy (and tense) time at the Justice Department as the Attorney General considered his political future, which led to his resignation from the Department in early September. |

|

|

|

|

|

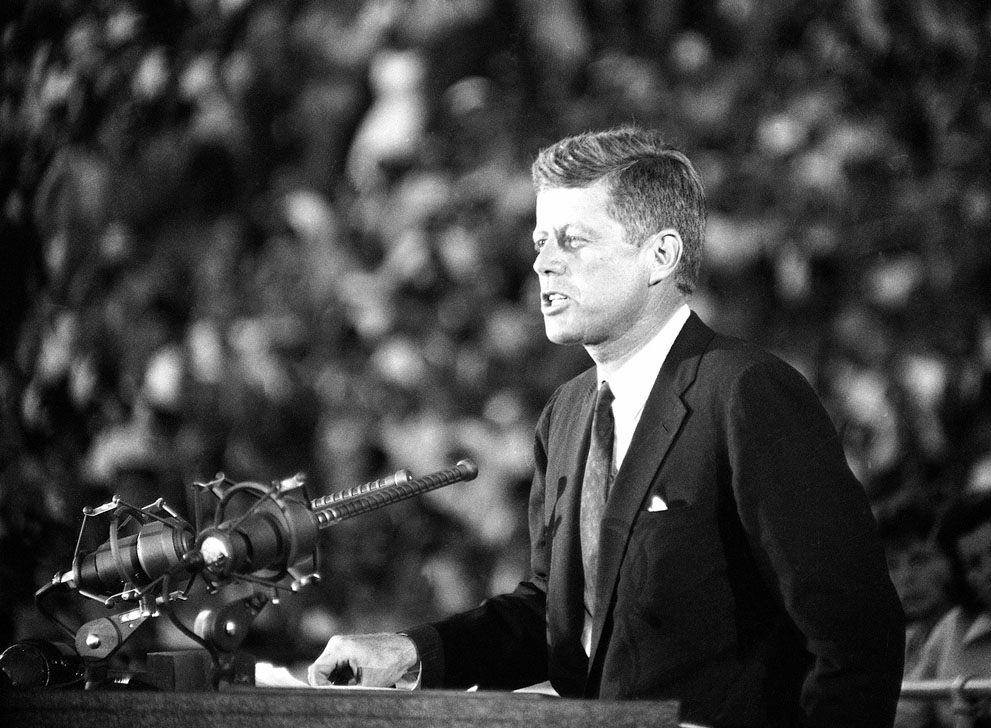

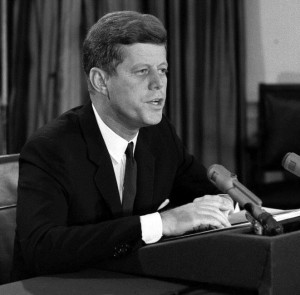

ELECTION DAY! JFK In a midterm election just like this one, JFK in 1962 used televised remarks to remind the nation to VOTE! |

|

|

|

|

| Response To Philip Shenon's Politico Article Regarding Robert Kennedy And The Warren Commission During his year-long campaign to trash the Warren Commission, Philip Shenon has consistently ignored the facts. In his recent Politico article about the Warren Commission’s decision not to ask Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy for sworn testimony, Shenon continued this practice by failing to acknowledge the pertinent facts set forth in my book (pp. 184-88) based on the documents and personal journal which I put online last year. As a result, he erroneously concluded that the Attorney General refused to provide sworn testimony to the Commission – either by affidavit or appearance before the Commission. On May 22, 1964, the Commission’s general counsel, Lee Rankin, “instructed me to talk with the Attorney General about his proposed statement to be submitted to the Commission.” I do not know why he referred to a statement rather than sworn testimony. When I discussed this matter initially with Ed Guthman (the Department’s public information officer) on May 28, however, Ed and I considered “the appropriateness of an appearance of the Attorney General before the Commission or a statement in which he would express his confidence in the Commission and inform the Commission that he has no evidence in his possession of any domestic or foreign conspiracy.” Guthman thought that such a statement by the Attorney General might “reduce the need for the Attorney General to make a statement to the public after the report of the Commission is published.” |

|

Meeting with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy(RFK) and J. Edgar Hoover(JEH), Directore of the Federal Beareau of Investigation(FBI), 10:12AM |

|

| On June 2 Guthman told me that he had discussed the matter with the Attorney General and that I should draft a statement along the lines of our earlier discussion. The result was the draft “Statement of Robert F. Kennedy” attached to Shenon’s article. The first paragraph of the statement refers to the Attorney General “having been duly sworn,” but the final paragraph does not include the usual provision where the person swears or affirms that the facts set forth in the affidavit are truthful. I brought this statement/affidavit to my meeting with Guthman and Deputy Attorney General Katzenbach the next day, June 3, where it was promptly rejected as “sterile and unsatisfactory.” At this meeting Katzenbach proposed “a third alternative” – this would consist of an exchange of letters between the Commission and the Attorney General. According to my journal, Katzenbach thought that an appropriate letter from the Attorney General “would meet the needs of the Commission and also justify a decision by the Commission not to call the Attorney General as a witness.” Neither Katzenbach nor Guthman perceived any other purpose for the Attorney General to appear before the Commission. He had not been in the motorcade (unlike Mrs. Kennedy, President Johnson, and his wife); the Department of Justice (unlike State and Treasury) was not defending actions taken by department officials (other than the FBI) relating to Oswald; and J. Edgar Hoover had already testified about the FBI’s relationship with Oswald and its investigation of the assassination, as would the heads of the CIA and Secret Service. We decided to pursue Katzenbach’s approach of an exchange of letters and to schedule a meeting with the Attorney General as soon as possible. |

|

I brought a draft letter for the Attorney General to consider at our next meeting on June 4, 1964. Although he did not express a desire to testify before the Commission, Robert Kennedy said that he was “willing to do anything necessary for the country and thought that his making a statement about the non-existence of a conspiracy would be desirable.” He pointed our an error in my draft letter in that “he had never received any reports from the F.B.I. in regard to the assassination and that his only sources of information about the investigation were the Chief Justice, Deputy Attorney General Katzenbach and myself.” He said he was otherwise satisfied with the draft and we concluded the meeting with the understanding that he and Warren would exchange letters and that this would fully meet the Commission’s needs. This is what was done. I brought a draft letter for the Attorney General to consider at our next meeting on June 4, 1964. Although he did not express a desire to testify before the Commission, Robert Kennedy said that he was “willing to do anything necessary for the country and thought that his making a statement about the non-existence of a conspiracy would be desirable.” He pointed our an error in my draft letter in that “he had never received any reports from the F.B.I. in regard to the assassination and that his only sources of information about the investigation were the Chief Justice, Deputy Attorney General Katzenbach and myself.” He said he was otherwise satisfied with the draft and we concluded the meeting with the understanding that he and Warren would exchange letters and that this would fully meet the Commission’s needs. This is what was done.Shenon’s accusation that the Attorney General refused to provide sworn testimony is not supported by the facts. He was never asked to do so. Furthermore, if he had testified or provided an affidavit, there is no doubt that he would have denied having any knowledge of a conspiracy as he did in his letter– because in fact he had no such information. Shenon should return to the National Archives and pursue his search for further documents – a more productive use of his time than regurgitating decades-old allegations of suspicions and non-existent conspiracies. As for my archives, you can find them here. |

|

|

|

|

|

9/11 - Never Forget, large and small The attacks on September 11th, 2001 form for many of us an indelible memory that separates history into two periods: before 9/11 and after. In that respect, for my generation, September 11, 2001, was similar to November 22nd, 1963, the day JFK was assassinated. We all know people who were personally affected by the attacks on 9/11, and we are all aware that the geopolitical implications of 9/11 continue to be felt. Yet tragedies such as 911 are intensely personal as well, a fact I was reminded of by this ESPN piece about Welles Crowther, a former college Lacrosse player who was at work in the South Tower on 9/11/01. This heroic man saved a dozen people from dying in the collapsing building, at the cost of his own life.  |

|

|

|

|

|

JFK Campaigns for the presidency in Texas (1960) “On September 12, 1960, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson touched down in Texas for a couple days of campaigning. This rare film captures the campaign as it travels through Forth Worth and Dallas, stopping in parks and parking lots as Kennedy addresses unexpectedly large crowds. While most of this film is without audio, there is a segment of JFK’s speech in Burnett Park in Ft. Worth that can be heard. In it, JFK responds to Republican accusations that he is not a true member of the Democratic party. The crowd responds enthusiastically.” Quote and video Courtesy of Texas State Archive: http://texasarchive.org/  |

|

|

|

|

|

World War II and its Impact on JFK This week marks 75 years since Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and began World War II.  Approximately 60 million people would die in the war, making it the deadliest in human history. Additionally, WWII saw the redrawing of international borders, vast shifts in world power, and the emergence of the USA vs. USSR dynamic that would dominate the next four decades. (2) Approximately 60 million people would die in the war, making it the deadliest in human history. Additionally, WWII saw the redrawing of international borders, vast shifts in world power, and the emergence of the USA vs. USSR dynamic that would dominate the next four decades. (2) |

|

WWII was also immensely influential in the life of President John F. Kennedy. Like so many other young men from all walks of life, Jack VOLUNTEERED for active military duty following the deadly Japanese attacks on the US Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. (1) WWII was also immensely influential in the life of President John F. Kennedy. Like so many other young men from all walks of life, Jack VOLUNTEERED for active military duty following the deadly Japanese attacks on the US Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. (1) |

|

| According to the JFK Presidential Library: Commanding the Patrol Torpedo Craft (PT) USS PT 109, Lieutenant, Junior Grade, John Kennedy and his crew participated in the early campaigns in the Allies’ long struggle to roll back the Japanese from their conquests throughout the island chains of the Pacific Ocean. The role of the small but fast PT boats was to attack the Japanese shipping known as the “Tokyo Express” that supplied Japanese troops in the islands, and to support the U.S. Army and Marine Corps attacking the Japanese on shore. (1) |

|

The future President faced his most harrowing experience of the war on August 2, 1943. That night, while his PT boat was “running silent”, a Japanese destroyer literally cut JFK’s ship in two. The future President faced his most harrowing experience of the war on August 2, 1943. That night, while his PT boat was “running silent”, a Japanese destroyer literally cut JFK’s ship in two.According to the library, “Kennedy towed injured crew member McMahon 4 miles to a small island to the southeast. All eleven survivors made it to the island after having spent a total of fifteen hours in the water.” (1) With the help of some courageous native islanders, JFK and his crew were thankfully able to return to their comrades. |

|

| The experience of going to war can profoundly shape one’s perspective. Those who have fought and seen their comrades suffer and fall around them appreciate the human costs of distant wars. It is no longer as common as it once was for American politicians to have active military experience (3). With no experience of the hardships of war, our current politicians may be too eager to send others’ children to fight for questionable purposes. Do you agree? Comment on my FB page and let me know! Sources: 1. http://www.jfklibrary.org/Exhibits/Past-Exhibits/JFK-in-WWII.aspx 2. http://www.cnn.com/2013/07/09/world/world-war-ii-fast-facts/ 3. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-fix/wp/2013/11/11/the-long-decline-of-veterans-in-congress-in-4-charts/ |

|

|

|

|

|

Ferguson and the Civil Rights Movement |

| Until two week ago, the town of Ferguson, MO was mostly unknown by those not living in the St. Louis metropolitan region. That all changed on Aug. 9, when an eighteen year-old African American young man named Michael Brown was fatally shot by a local Ferguson PD officer named Darren Wilson[1]. What transpired to cause Brown’s death remains unclear and hotly-debated. The police claim “Brown physically assaulted the officer, and during a struggle between the two, Brown reached for the officer’s gun. One shot was fired in the car followed by other gunshots outside of the car”[1] Some local community members contest this version of events. They believe the killing of Michael Brown reflects widespread racial discrimination against their community on the part of police. They point to other incidents where unarmed African Americans have been victims of violence, from police or self-appointed vigilantes like George Zimmerman. [1] This tension between community and police erupted in several nights of violent clashes in the week after Brown’s death. On Aug. 13, the police threw “tear gas at protesters in Ferguson in order to disperse crowds. During the commotion, police also force media to move back out of the area and throw tear gas at an Al Jazeera America crew.” [1]  Although we have come a long way since Jim Crow, I am sad to say that in this arena, not enough progress has been made since the 1960s. President Kennedy in many ways pioneered civil rights protections under law and thought long and hard about the most effective ways that he could use Federal power to enforce equal treatment under the law. Although we have come a long way since Jim Crow, I am sad to say that in this arena, not enough progress has been made since the 1960s. President Kennedy in many ways pioneered civil rights protections under law and thought long and hard about the most effective ways that he could use Federal power to enforce equal treatment under the law.The most notable example occurred early in JFK’s presidency, when the University of Alabama was forced to racially integrate, a move opposed by the Governor of Alabama. President Kennedy had to decide to what extent to intervene. Amazingly, this decision was captured on camera by documentarian Robert Drew. Here, we can watch JFK consider this exact question. Ultimately, JFK took action. He sent National Guard troopers to Alabama to ensure the safety of the first Black students at the University. He also proposed the foundation of the Civil Rights act of 1964 – which provided that businesses of public accommodation, like restaurants and hotels, could not racially discriminate. President Johnson signed that bill into law after JFK was assassinated. You can see JFK’s historic Civil Rights Address where he announced his decision to send the National Guard to protect African American students and called on Americans everywhere to end discrimination in its entirety here: JFK would have been proud to see his Civil Rights bill enacted, but he would be disappointed with the lack of other progress, such as closing the income, life-expectancy and life-outcome gaps he discusses in his video. [1] http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/08/14/michael-brown-ferguson-missouri-timeline/14051827/ |

|

|

|

|

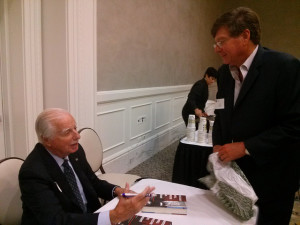

| MY EXPERIENCE IN PROMOTING "HISTORY WILL PROVE US RIGHT" Spending the summer on our farm in Western New York has provided the opportunity – between chores – to reflect on my book tour during the past year to discuss my book about President Kennedy’s assassination, “History Will Prove Us Right: Inside the Warren Commission Investigation into the Assassination of John F. Kennedy.”  The most unanswerable question from the audiences at my 26 events in 11 states? What was Lee Harvey Oswald’s motive in killing President Kennedy? In all the time the Warren Commission and its staff spent investigating the assassination, and even with the assistance of three expert psychiatrists, we never could get to a conclusion about motive that we could support with evidence. Some of us speculated one way or another; but no one could be sure. Oswald never explained himself, even to his wife, and his meandering comments in his “Historic Diary” provided clues that simply prompted more debate. The most unanswerable question from the audiences at my 26 events in 11 states? What was Lee Harvey Oswald’s motive in killing President Kennedy? In all the time the Warren Commission and its staff spent investigating the assassination, and even with the assistance of three expert psychiatrists, we never could get to a conclusion about motive that we could support with evidence. Some of us speculated one way or another; but no one could be sure. Oswald never explained himself, even to his wife, and his meandering comments in his “Historic Diary” provided clues that simply prompted more debate.The second most unanswerable question? Why couldn’t the Secret Service agents in the motorcade see the shooter at the window of the Texas Book Depository when bystanders on the parade route saw him clearly enough while he was aiming (and shooting) his rifle to describe him for the police? Based on this description Officer Tippit stopped Oswald on the street shortly after the shooting, and Oswald pulled his revolver and shot Tippit before fleeing to the movie theater where he was arrested. One of the most difficult investigative tasks our Warren Commission staff faced was prying information from the Treasury Department where the Secret Service was located in those days. They were determined to protect their agents from blame for the President’s death and never shared the detailed internal report (about what went wrong and what remedies were required) with the Commission. Without this information, the Commission’s recommendations about Presidential protection lacked the hard-hitting specifics that might have led to meaningful recommendations to reform the organization. People would ask me about one or more of the better-known conspiracy theories, and these are readily resolved by reference to scientific and investigative facts. I would tell them what I thought. Only a few conspiracy advocates took the occasion to challenge me in person. For the most part, I think, this was due to the fact that those who came to hear me tended to be older than 50; and most of these had some personal recollections of the day on which President Kennedy was assassinated. As for those younger people who heard me speak, I had the sense that they were surprised by the attention being given to this historical event after 50 years and appeared to have no preconceptions about the assassination.  The audiences seemed eager to hear from someone who had personally participated in the work of the Commission. They seemed to enjoy the opportunity to question me about aspects of my experience on the Commission staff and I, in turn, enjoyed the opportunity to respond. The fact that I am still alive – and prepared to defend the Commission’s work – appeared to win me at least the initial support of many listeners. My reference to the subsequent and impressive careers of my colleagues on the Commission staff also seemed to support my assertion that we were all committed to a thorough and independent examination of the assassination. I found that my audiences were generally unaware of the extent to which the Commission’s principal conclusions had been revisited over the last several decades and, without exception, have been reaffirmed. I described the last chapter of my book, where I summarized the many investigations since 1964 examining one or more aspects of our investigation – in particular the work of the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1978-79 – and the confirmation of the Commission’s conclusions that Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin and there was no credible evidence of any conspiracy. I pointed out that the critics of the Warren Commission’s conclusions typically ignore these subsequent investigations, which I believe does more to impeach their credibility than anything I might say. The audiences seemed eager to hear from someone who had personally participated in the work of the Commission. They seemed to enjoy the opportunity to question me about aspects of my experience on the Commission staff and I, in turn, enjoyed the opportunity to respond. The fact that I am still alive – and prepared to defend the Commission’s work – appeared to win me at least the initial support of many listeners. My reference to the subsequent and impressive careers of my colleagues on the Commission staff also seemed to support my assertion that we were all committed to a thorough and independent examination of the assassination. I found that my audiences were generally unaware of the extent to which the Commission’s principal conclusions had been revisited over the last several decades and, without exception, have been reaffirmed. I described the last chapter of my book, where I summarized the many investigations since 1964 examining one or more aspects of our investigation – in particular the work of the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1978-79 – and the confirmation of the Commission’s conclusions that Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin and there was no credible evidence of any conspiracy. I pointed out that the critics of the Warren Commission’s conclusions typically ignore these subsequent investigations, which I believe does more to impeach their credibility than anything I might say. |

|

|

|

|

| JFK, The Cold War, and Vladimir Putin Despite a crowded news docket, Russian aggression in the Ukraine region continues to draw the attention of the world. Under the Presidency of Soviet-throwback and former KGB officer Vladimir Putin, Russia has undertaken an expansionist mode not seen since the end of the Cold War. Indeed, given Putin’s Soviet background, the comparisons are inevitable—and prompt the question of how President Kennedy might have handled the current situation. Age of Soviet Expansion Back in the early 1960s, the USSR was assertively in expansion mode. Across Asia, China, Eastern Europe, South America and the Caribbean, the Communist system of government was gaining footholds. These developments were met with concern and attempted counter-measures by the Eisenhower administration, but the global situation was becoming increasingly unfavorable.  President Kennedy took it on himself to reverse this trend. According to the JFK Presidential Library, he “ordered substantial increases in American intercontinental ballistic missile forces… added five new army divisions and increased the nation’s air power and military reserves”. President Kennedy took it on himself to reverse this trend. According to the JFK Presidential Library, he “ordered substantial increases in American intercontinental ballistic missile forces… added five new army divisions and increased the nation’s air power and military reserves”.Cuban Missile Crisis The single greatest test Kennedy faced as President came when the USSR began to install nuclear missiles in Cuba, a move that would have fundamentally altered cold war strategic calculations. President Kennedy simply could not allow nuclear missles 90 miles off of the coast of Florida. President John F. Kennedy addresses a worried nation during the Cuban Missile Crisis President Kennedy ordered a blockade of Cuba, and after a tense showdown with his Soviet counterpart, Nikita Khrushchev, the Russians removed the missiles in return for an American promise not to invade Cuba.  Foreign Engagement Foreign EngagementWhen it came to fighting outside of the American sphere of influence, JFK was more cautious about committing force. He sent a small military contingent to Vietnam, but said “In the final analysis, it is their war. They are the ones who have to win it or lose it. We can help them, we can give them equipment, we can send our men out there as advisers, but they have to win it—the people of Vietnam against the Communists.” Moving Forward President Kennedy walked a line; defending our homeland, while not getting American forces entangled in extended war campaigns. Presidents Johnson and Nixon after him escalated the War in Vietnam to the extent that it became a national quagmire. This in turn helped influence Nixon and Kissenger to seek détente and arms reduction as their chief strategy to contain the Soviet threat. In what ways is today’s global strategic balance like the Post-Vietnam era? Do you think President Obama is constrained in his options in confronting Putin’s Russia because of the aftermath of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars? What do you think JFK would do differently?  Sources: http://www.jfklibrary.org/JFK/JFK-in-History/The-Cold-War.aspx http://www.jfklibrary.org/JFK/JFK-in-History/Vietnam.aspx http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/ukraine-crisis/russians-are-coming-putins-end-game-ukraine-n191521 |

|

|

|

|

|

One Giant Leap ... Reflections on the 45th Anniversary of the Moon Landing |

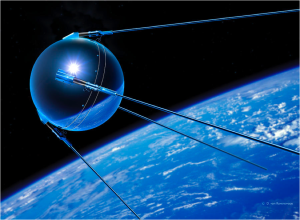

| Introduction This week marks the 45th anniversary of the historic Apollo 11 Moon landing. It is hard to overstate the impact of this event to the world at the time; the moon landing was a major victory for America in the space race between the US and USSR, and was a moment shared with the entire nation through the expanding medium of television. The moon landing holds even additional significance for my generation as it represented the fulfillment of President Kennedy’s bold promise that America would land on the moon before the 1970s. So much of our space program owes its existence and success to President Kennedy. Space Race:  The USSR fired the opening salvo in the space race in 1957 with the dramatic and successful launch of the world’s first artificial satellite- Sputnik. The USSR fired the opening salvo in the space race in 1957 with the dramatic and successful launch of the world’s first artificial satellite- Sputnik.Given the incredible cold war tension between the two superpowers at the time, the idea of the Soviet Union gaining a significant military advantage through space was deeply troubling. In response, President Eisenhower initiated Project Mercury, and selected the first American Astronauts. Yet the US continued to be outpaced- the USSR was first to put a man in space in 1961. JFK Makes a Difference President Kennedy refused to allow the United States to fall permanently behind in the space race. He asked Congress for nearly $10 billion in additional funding for NASA. The successes began to roll in on the American side. John Glenn, Jr. because the first American in space in 1962. But President Kennedy was not satisfied with matching Soviet accomplishments. In a speech at Rice University on September 12, 1962 – less than a year after we first placed a man in orbit- President Kennedy pledged that the USA would land a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s. Impact  Under Presidents Johnson and Nixon, the United States continued to gain the advantage in the space race. The 8th mission of the new Apollo program – Apollo 8—was the first manned mission to orbit the moon. The entire space race culminated in the Apollo 11 moon landing. Fulfilling JFK’s vision, Neil Armstrong, and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin Jr. became the first men to walk on the moon, while Michael Collins piloted the craft in orbit. Under Presidents Johnson and Nixon, the United States continued to gain the advantage in the space race. The 8th mission of the new Apollo program – Apollo 8—was the first manned mission to orbit the moon. The entire space race culminated in the Apollo 11 moon landing. Fulfilling JFK’s vision, Neil Armstrong, and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin Jr. became the first men to walk on the moon, while Michael Collins piloted the craft in orbit.Though JFK did not live to see his vision realized, I believe he would be extremely proud of the United States victories over the USSR in the space race and the entire Cold War. Where do you think the space race falls on the list of JFK’s accomplishments? Comment on my FB page HERE!

|

|

|

|

|